Offshore crew transfer demand is expected to recover quickly in the oil and gas sector.

Is the industry ready with modern, safe and fit-for purpose solutions to accommodate growth? Is the wider energy industry really doing all it can in terms of maximising the safety of offshore personnel?

We take a look at fleet utilisation, spare capacity, and point to some potential areas for improvement in the offshore crew transfer industry.

H175 Operated by Offshore Helicopter Services UK Ltd departing Aberdeen for CNOOC's Golden Eagle offshore oilfield on November 3rd, 2021

Leading Market Indicators are Positive

After seven difficult years of downturn for the oilfield services business, things are looking up. Oil prices are high and supported by low investment in capacity in recent years and strong demand. War in Ukraine has added a further complexity and will likely spur additional upstream investment on a ‘security of supply’ basis. Substantial uplifts in Capital Expenditure (Capex) this year are seeing rigs and people return to work, and new projects are finally being sanctioned.

Up to this point, the seven years prior have seen a near complete hiatus in new orders of new equipment to service the offshore industry (vessels, rigs, helicopters) and most asset-heavy sectors have suffered from over-capacity and aggressive price competition to secure work.

The oil and gas companies and more recently the offshore wind companies rely on the offshore supply chain to provide new technology, but there has to be an appetite to (a) use it and (b) pay for it.

This produces something of a dilemma for original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) – if the development period for new technology is long (and in aviation it can span decades), how can they get comfort their investment will be repaid in the long run through sales of new equipment?

In Search of the ‘Holy Grail’'

End users, of course, want the ‘holy grail’ – in current times they want to do everything cheaper, safer, faster and with decreased harmful emissions to the environment. There is no doubt that latest technology is making headway in all of these areas, albeit not always all of them at the same time.

So, as the offshore industry recovers, it is likely that we will reach a point in each of the oilfield equipment markets where spare available capacity is eroded to the point where either:

Idle/stored old equipment is reactivated (at a cost) or

New equipment is ordered from OEMs.

The ‘holy grail’ aims start to diverge at this point. Reactivation of old equipment will likely be quicker and cheaper than newbuild but will come at the cost of higher emissions and without the latest developments in safety.

Offshore Safety - Can the Industry Do Better? How Many Aircraft are Available?

Which of these ‘holy grail’ aims is most important? Most marketing departments in oil majors and offshore wind companies are hammering the environmental message hard, whether it is emissions reductions schemes, offshore windfarm projects or investment in the fuels of the future (hydrogen or whatever is flavour of the week at the time….) This is evident through their presentations at industry events and through the messaging on corporate websites. This doesn’t mean that the important ‘key performance indicators’ of capital efficiency, safety and delivery on time have been lost, however we would start to question – can they do better?

Let us take offshore helicopters as the first example. In 2020 the International Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP) Aviation Safety Group published its latest guidelines on safety (see more here). Essentially the R690 document was looking to set a baseline on safety in terms of a number of areas concerning aircraft specification, upgrades, crew training and operational procedures, amongst others. One key implication of the adoption of these guidelines (which are not enforced) would be the variety of choice of offshore helicopters. Only a small number of types (including S-92, AW189, H175, AW139, H160, AW169) would meet these requirements and thus only those aircraft would be expected to be bid on subsequent new contracts and contract renewals by IOGP members. Of the offshore fleet of just over 1,400 aircraft, only 620 (44% of the fleet) would meet the R690 standards.

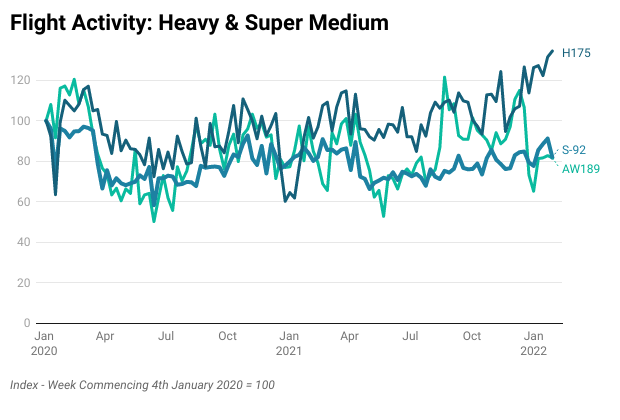

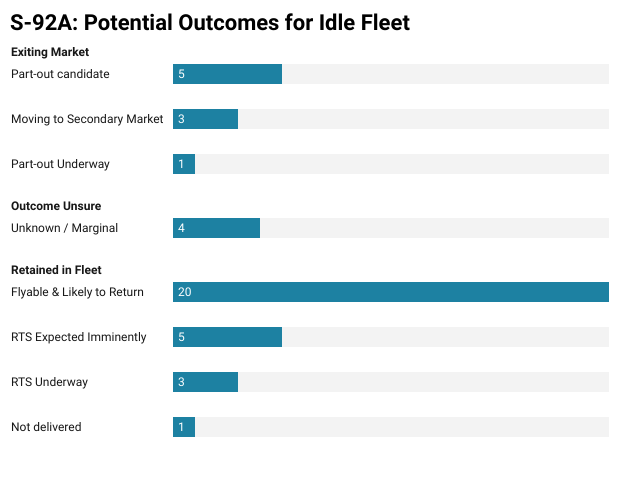

The number of available existing aircraft meeting those criteria is starting to fall. Our usual measure of demand considers aircraft known to be flying (‘active‘.) Of the inactive - a number of these will be on contract but in place as a backup or in long-term maintenance and to establish ‘effective utilisation‘ we take those aircraft into account. The Super-Medium aircraft (H175 and AW189) are effectively at or near full capacity. The AW139 has low storage levels and at HAI 2022 lessors were reporting they were sold out of AW139s until the end of the year. Even the S-92, which has been plagued by over-supply for years, may only have two dozen effective available aircraft in oil & gas (accounting for those already committed/likely to exit.)

Source: Heavy & Super Medium Offshore Fleet Census Q1 2022, Air & Sea Analytics

Orderbooks for offshore aircraft are very thin. Sikorsky hasn’t had a new offshore order for a number of years and likewise the Super-Medium offshore orderbooks, whilst not published, are also thought to be either zero for some models or near-zero for others. To meet incremental demand in the offshore market, the out-of-work S-92s are the only available real solution in the next 12-24 months for any requirement above 7T MTOW. (We do note that a number of H225s have been reactivated in China and Namibia in recent years however – the ability to replicate this elsewhere is likely to be limited by both the available aircraft remaining in usable oil and gas configuration and the appetite of the end users to fly it). Once these S-92s are committed (which could happen in as little as 12-24 months) there will need to be new orders of offshore helicopters to meet demand growth.

In the medium/light twin sector, there are few options and it seems that some operators, rather than ordering aircraft and waiting for delivery, are instead putting to work/reactivating older technology aircraft. This includes reactivations of S-76C++ in the Americas and a recent contract award featuring the AW109 by an oil major in Europe. Whilst these are no-doubt safe aircraft with a good track record, the basis of the design and certification dates back to the 1970s. (It is doubtful that many parents would choose to drive their children in cars built to 1970s safety standards.)

Austin Allegro - 1970s Automobile

Labour markets are tight and the ability to attract talented offshore personnel in the future may depend on the extent to which their employers choose to look after them. A cursory glance at the free cash flow of the top six oil majors will tell you that they can certainly afford the latest technology.

It is not all bad news – IOGP member Saudi Aramco have recently seen a major renewal programme on their medium fleet with 21 new AW139s delivered in the last 3 years, supported by lessor Milestone. Shell has supported the introduction to service of the new H160 model from Airbus with PHI in the Gulf of Mexico, which will begin flying from August 2022.

Offshore Windfarm Operators Are Mostly Using the Least-Safe, Most-Polluting Crew Transfer Solution

With a couple of exceptions, the offshore wind industry is almost exclusively using modern twins such as the AW169, the H135 and the H145 for heli-hoisting operations. Of greater concern is the environmental and safety implications of using crew transfer vessels instead of helicopters. There are some 3 dozen offshore wind rotorcraft in operation but over 480 offshore wind vessels. Based on modelling by Air & Sea Analytics, a windfarm 75 km from shore in the North Sea featuring 160 turbines would have associated annual emissions due to crew transfer for planned maintenance of over 2.5 million kg CO2 using vessels and would be expected to see 35 times the number of reportable incidents relative to a helicopter crew transfer solution (which for comparison would emit 825,000kg of CO2 per annum - less than a third of the vessel service). (Air & Sea Analytics has conducted extensive and detailed modelling of helicopter and vessel costs, emissions and safety for some of the worlds largest offshore players - contact us to discuss)

Whilst there is no doubt that offshore renewables projects don’t typically return the same margins as hydrocarbon projects, there is a window for certain projects (including the illustrative example above) where the helicopter is not just the fastest, safest and lowest emission option, it is also the most cost-effective. The offshore windfarm industry needs to decouple from the strong influence of the marine sector, take a step back and take a rational view of safety and emissions on a windfarm-by-windfarm basis.

Steve Robertson, Director

6th April 2022

Air & Sea Analytics